By Jonathan W. Rosen

New York Times

Reporting from Kapchorwa, Uganda

- Aug. 12, 2023

With

a mile to go in the 2017 World Cross Country Championships, Joshua Cheptegei

had one thing on his mind: win gold for his country on home soil.

It

was a balmy afternoon in the Ugandan capital of Kampala, and against a field of

far more seasoned athletes, he was closing in on his goal. Halfway through the

biennial event, in which the world’s top distance runners compete over 10

kilometers of grass, mud and occasional barriers, he had gapped the field with

a surge so elegant that it looked like he was floating.

Two

hours earlier, his compatriot Jacob Kiplimo had hoisted the red, black, gold

and gray-crowned crane of the Ugandan flag after winning the under-20 race. The

raucous crowd, which included the Ugandan president, Yoweri Museveni, expected

Cheptegei to do the same.

Now he was hanging on for dear life, determined to prove

that Uganda, long overlooked in the distance running world, could hold its own

against the sport’s powerhouses, Kenya and Ethiopia. But the storybook ending,

on this day, would not come to pass: In the final half-mile, as his body fended

off dehydration, Cheptegei’s engine sputtered. He slowed to an agonizing

shuffle, coming in 30th out of 136 finishers.

Cheptegei’s

near-triumph would nonetheless prove to be a prelude to a Ugandan running

renaissance. Two years later, he won the 2019 World Cross Country Championships

in Denmark. Uganda’s men took the team title.

Since then, Cheptegei has secured his place on the list of

distance running’s all-time greats, with an Olympic gold medal and two World

Championship titles on the track, as well as world records in the 5,000 and

10,000 meters. Kiplimo, who dethroned Cheptegei as the current World Cross

Country champion in February, now holds the half-marathon world record.

In 2019, Halimah Nakaayi won the World

Championship title in the 800 meters, and, in 2021, Peruth Chemutai won the

Olympic gold medal in the 3,000-meter steeplechase.

Cheptegei, left, won the gold medal in the 10,000 meters at the World

Athletics Championships last year, and fellow Ugandan Jacob Kiplimo won bronze.Credit...Charlie Riedel/Associated Press

In and around Kapchorwa, a small town in the foothills of

Mount Elgon, a 14,000-foot extinct volcano that straddles the Kenyan border,

hundreds of youngsters are hitting the roads with dreams of future glory.

Though Uganda’s volume of talent still lags behind that of Kenya and Ethiopia,

the magnitude of its rise has been remarkable.

“Every year, as a country, we’re getting better and

better,” Cheptegei said on an April afternoon, as he looked ahead to defending

his 10,000-meter title at this month’s World Athletics Championships in

Budapest. “The Mount Elgon region has always been home to running talent, and

we’re only just beginning to showcase it.”

Uganda’s

ascent, in many ways, is an outgrowth of longstanding success in Kenya. Since

1964, that country has won 105 Olympic medals in running events from 400 meters

to the marathon; Kenya has also produced six of the 10 fastest male marathoners

in history, and five of the 10 fastest women.

These

exploits have been mainly concentrated among the Kalenjin, a community of nine

closely related tribes descended from pastoralists that migrated south over the

last few thousand years from the Nile River Valley. Most of the seven million

Kalenjin today live in Kenya’s western highlands, where altitudes ranging from

6,000 to 9,000 feet help them develop more oxygen-carrying red blood cells and

greater lung capacities. Research has also shown that Kalenjin, on average,

have especially thin lower legs and a high leg-length-to-torso ratio, which

facilitates greater running economy, or the ability to make more efficient use

of oxygen.

There are Kalenjin in Uganda, too, and if it weren’t for

the quirks of colonial history, there would be more: The original borders of

Britain’s Uganda Protectorate, hashed out by mustachioed bureaucrats in 1894,

encompassed the bulk of the Kalenjin territory that is part of Kenya today.

Adjustments to the boundary in 1902, driven by the desire to unify

administration of a railway from the coast, unwittingly paved the way for

Kenya’s future running triumphs. Yet the new line, which cut through the crest

of Elgon, severed one Kalenjin tribe, the Sabaot, in two. The descendants of

those left in Uganda, who number roughly 300,000, live primarily in three

districts on Elgon’s western flanks — an area of striking natural beauty known

for its waterfalls, sweeping vistas and alpine forests.

A dirt road in the Kween District of Uganda leads to the forested upper

slopes of Mount Elgon, where the grandparents of many current athletes hunted

antelope and buffalo.Credit...Jonathan W.

Rosen

It

is here that Ugandan running is now thriving, though the region’s talent took

time to develop. While Kenya enjoyed relative stability in the decades after it

gained independence in 1963, Uganda was at war for much of the 1970s and 1980s.

Lawlessness pervaded the Mount Elgon region until the turn of the century:

Bandits from neighboring tribes would sweep in at night and conduct raids on

cattle, often killing locals in the process.

The

area was also slow to modernize. Until the 1990s, the ancestors of many current

athletes, including Cheptegei, Kiplimo and Chemutai, lived inside the forests

of Elgon’s upper belt, part of a small group of Sabaot that subsisted on milk,

honey and meat from antelope and buffalo they hunted. Here, 9,000 feet up,

there were no roads or schools, and no pipeline into competitive athletics. But

according to Moses Kiptala, an elder who grew up in this community, endurance

was of great value: The group’s method of persistence hunting involved chasing

animals for hours until they overheated.

Kiplimo,

who comes from a family of runners and had planned to contest the 5,000 and

10,000 meters in Budapest before being sidelined by an injured hamstring, is of

particularly distinguished stock. Kiptala recalls Kiplimo’s grandfather being

such a prolific hunter that the community called him Simba, or Lion.

Much

had changed by the time today’s stars were born: In 1983, Uganda’s government

began resettling the group, known as the Mosopisiek, downslope from the forest

to make way for a national park. Most are now small-scale farmers. The

resettlement process, Kiptala said, was traumatic, but it also helped unlock

running talent. Through school, children could access competitions, and by the

early 2000s, athletes from the Elgon region were beginning to appear in World

Championship and Olympic finals.

Uganda’s first champion of this period was a runner from

the country’s north, Dorcus Inzikuru, who won the 3,000-meter steeplechase at

the 2005 World Championships in Helsinki. Elgon’s watershed moment came seven

years later, when the Kapchorwa native Stephen Kiprotich notched an upset win

in the 2012 London Olympics marathon — the country’s first Olympic gold since

1972. He doubled down with a marathon title the following year in Moscow.

“Many Kenyans were saying London was a fluke, so I had to

prove them wrong,” Kiprotich said.

Image

Peruth Chemutai, second from left, won a gold medal at the Tokyo Olympics

in the 3,000-meter steeplechase.Credit...Jonathan

W. Rosen

Among

the legions inspired by those performances was a teenage Cheptegei, who had

also grown up in Kapchorwa with dreams of running glory. His parents, who

insisted that he enroll in college, were skeptical. But his progress,

highlighted by a 10,000-meter world junior title, was so impressive that even

President Museveni urged him to drop the books and focus full-time on

athletics.

Like

many Ugandan runners before him, Cheptegei left for Kenya, where there were

more elites to train with and more sophisticated coaching. In 2016, determined

to raise the sport’s profile at home, he persuaded his management, the

Netherlands-based Global Sports Communication, to establish an elite group in

Kapchorwa.

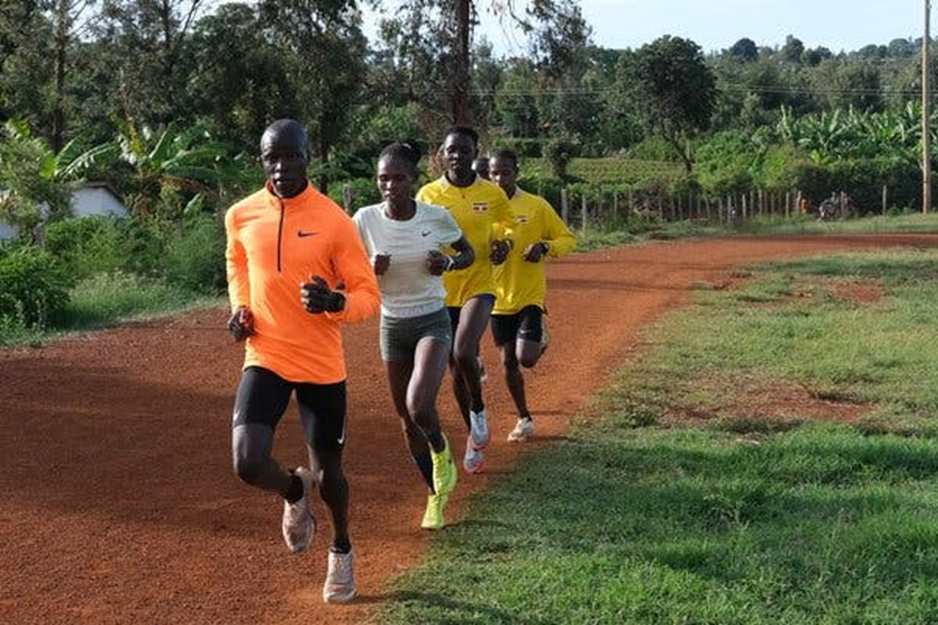

Seven

years later, Cheptegei is not only a national icon, he’s also a force for

talent development. Along with coach Addy Ruiter, he’s pieced together a squad

of two dozen globally competitive athletes, who live together in a

stone-and-brick facility known as the Joshua Cheptegei Training Center, on the

slopes above the town. An affiliated camp for up-and-coming junior athletes is

a short drive away in Kween, a neighboring district.

Other management groups, including Kiplimo’s Italy-based

Rosa & Associati, have opened camps in the area as well, drawn both to the

concentration of talent and the training environment. Though Kapchorwa sits at

a slightly lower altitude than the main training hubs in Kenya and Ethiopia,

the town’s location halfway up a mountain enables greater versatility. Ruiter,

a 60-year-old former triathlete who left a desk job at Ikea to move here from

the Netherlands in 2019, said his athletes benefit from long runs that reach as

high as 10,000 feet, as well as faster sessions at altitudes as low as 3,500

feet.

While a structure for continued success is now in place,

Ruiter was quick to stress that the size of Uganda’s talent pool will never

quite measure up to Kenya’s or Ethiopia’s. He also described Cheptegei and

Kiplimo as “once-in-a-generation talents” and said it could be a while before

Uganda sees another athlete of their caliber. Eventually, though, he believes

more champions from Mount Elgon will emerge.

Addy Ruiter, left, moved from the Netherlands to Uganda to coach runners

with Cheptegei.Credit...Jonathan W. Rosen

For

Cheptegei, the focus is now on the World Championships in Budapest: He’s

expected to contend for the 10,000-meter title on Aug. 20 and may double back

to vie for the podium in the 5,000 meters as well. And in December, he will

make his marathon debut in Valencia — the same city where he set his

10,000-meter record in 2020. Kiplimo has plans to eventually move up to the

marathon, too, where the money is greater and new record-breaking opportunities

await.

On that day in April, as he spoke from inside his camp

after the day’s training session, Cheptegei said he was simply grateful for the

journey that he and his country had taken so far — even the rare occasions when

things hadn’t quite worked out.

“It’s one of those incidents that built me mentally,” he

said of the 2017 race in Kampala. “I had two options: Allow it to break me; or

gather myself together and build an inspirational story.”

The Joshua Cheptegei Training Center, which sits above the town of Kapchorwa at an altitude of 8,200 feet, was completed in December 2022 and hosts two dozen elite runners.Credit...Jonathan W. Rosen

Subscribe to the New York Times: The New York

Times: Digital and Home Delivery Subscriptions (nytimes.com)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/63EIKLLTM5FIPCGSO65XRUFLAI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/KFHVMFZGC5CCJMAYDF4RF3UV6E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/LPSY3IYALFF4ZBBHIL6GMFKWTQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/JB6PL7TMUVAFPMXBZGIJAIC2FI.png)

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/pmn/c30df34c-ae3e-4798-a2c8-253579cc69d2.png)